Historical Sociolinguistics and Sociohistorical Linguistics

Up |

|

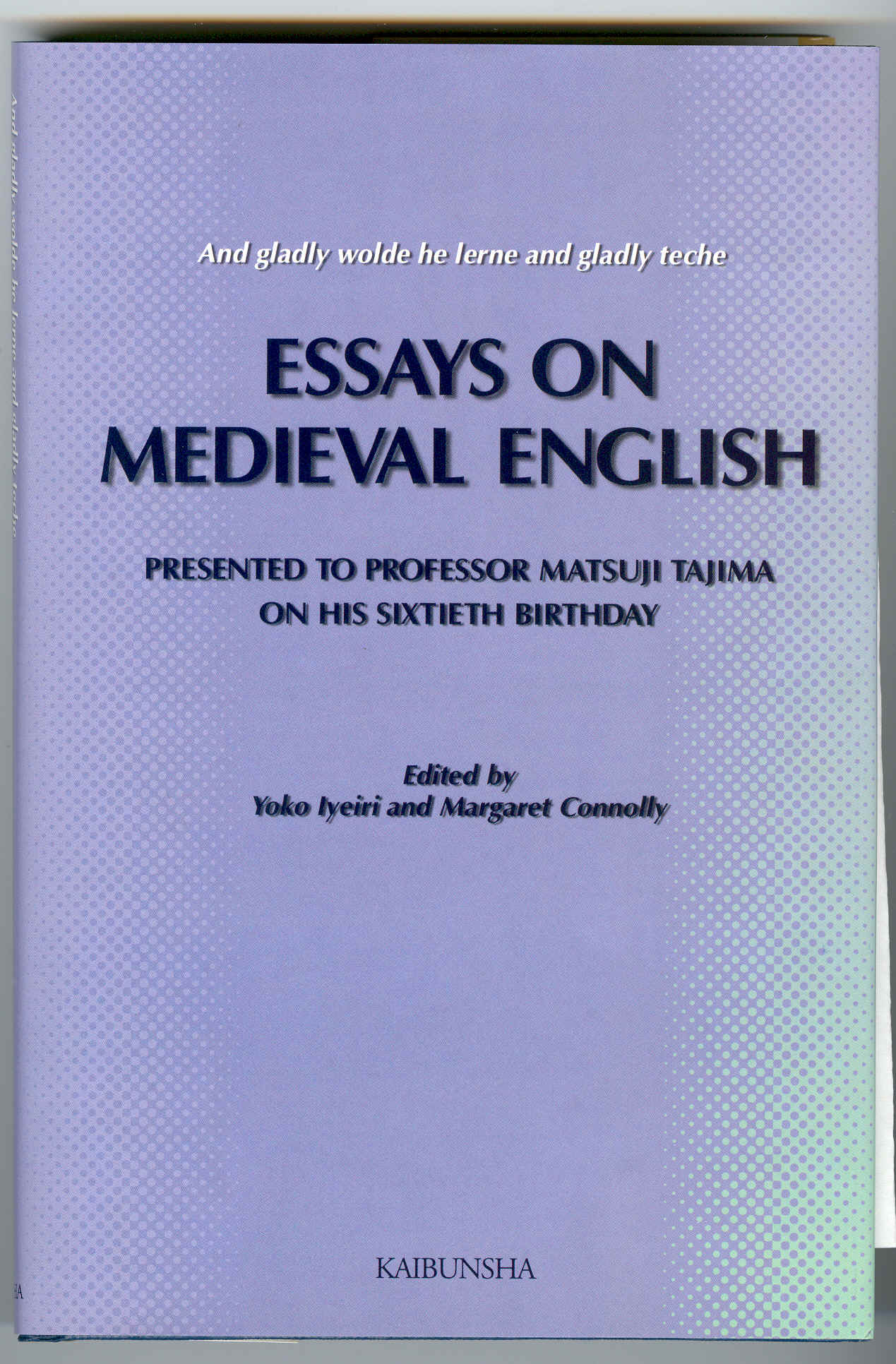

Review of: Yoko Iyeiri and Margaret Connolly (eds.). 2002. And gladly wolde he lerne and gladly teche. Essays on Medieval English presented to Professor Matsuji Tajima on his sixtieth birthday. Tokyo: Kaibunsha. xiv + 270 pp. (January 2004, HSL/SHL 4)

It

is always difficult to review a volume where the only unifying theme is the

person in whose honour it is compiled. As a tribute to years of outstanding

scholarship, it is a reflection of his or her scholarly interests as much as

those of his friends and colleagues. Essays onMedieval English fits this

description perfectly. The

volume under review comprises fourteen essays dedicated to Professor Matsuji

Tajima. Seven of these are devoted to mediaeval English language, while the

other seven concern mediaeval literature, and this division is reflected in the

structural layout of the volume. The book also contains a celebratory essay by

Professor E.F.K. Koerner and a list of published writings of Professor Tajima. The first of the fourteen, Hans Frede Nielsen's paper is intended to review the question of the origin of linguistic innovations Old English shares with its continental relatives. Jeremy J. Smith tries to interpret Old English breaking as a contact-induced process, originating at the Anglian-West Saxon dialectal interface. Eric G. Stanley uses the example of OE deofol ‘devil’ to analyse some peculiarities of definite article usage. The indication of degrees of truth in Chaucer's Troilus and Criseide is discussed by Yoshiyuki Nakao, who concentrates in his paper of the uses of the modal adverb trewely. Syntactical studies are represented by Sadahiro Kumamoto, who analyses the function of various word classes as they occur in rhyme position, using as his source the Middle English translation of The Romaunt of the Rose compared with its Old French original. Yoko Iyeiri's paper can also be classified as syntactic, as its subject matter is the decline of multiple negation and its connection to the development of non-assertive any. The seventh and final linguistic study in the volume has been contributed by Thomas Cable, who argues for a re-evaluation of the metre of Lydgate and Hawes, demonstrating - unlike many of his predecessors - its regular nature. The literary studies are equally diversified. Old English is represented by Yun Terasawa's cameo devoted to the interpretation of the phrase æfter wiste in Beowulf 128. Laurence McEldregdeanalyses medical writings of Benvenutus Grassus and compares them with other contemporary texts to establish whether this thirteenth-century ophthalmologist ever lectured at the university of Montpellier. Robert E. Lewis explains some of the principles of manuscript interpretation as adopted in the Middle English Dictionary, such as the double-dating system or the peculiar treatment of Chaucer editions. Troilus’s speech on the issue of predestination in Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseide is analysed by Joseph Witting, who sees its impact as predominantly philosophical and religious, sharing its context with its Boethian source. Margaret Connolly contributes to the volume an edition of the Middle English text The Eight Points of Charity, a derivative of the Contemplations of the Dread and Love of God, preserved in John Rylands University Library MS. English 85. The issue of the portrayal of King Arthur in mediaeval literature is taken up by Edward Donald Kennedy, who illustrates the rivalry between the concepts of a weak Arthur and a noble Arthur, as represented in texts for French and English audiences respectively. The final contribution in the volume is Hideki Watanabe's study of the origins and circulation of the Biblical phrase while the world standeth. The task of the reviewer, obviously, is not a mere compilation of an annotated table of contents. However, even this quick description shows that the volume is such a mixed bag, that it is virtually impossible to generalise about its content. Therefore, it seems more advisable to close this review with a more detailed discussion of one of the contributions, Jeremy J. Smith’s ‘The origins of Old English breaking’. The choice of this particular paper is dictated both by research interests of the reviewer and by the type of issues raised by the author. For

Smith, breaking should be treated as a language contact phenomenon. His argument

relies on a number of assumptions about the context and the phonetic nature of

the segments involved in the process, which in turn have implications of a more

general nature. The first of these, the rejection of w-breaking as

inconclusively evidenced, is very convincing and should be accepted as one of

the initial premises for this discussion. Subsequently, however, Smith supports

his theses with some rather specific phonetic interpretations. For l-breaking,

he argues that Anglian had acquired a velarised variety of /l/ through contact

with North Germanic dialects still in the pre-invasion period. This feature,

responsible for the lack of first fronting in Anglian dialects, would then be

adopted by the speakers of West Saxon on the grounds of prestige associated with

Anglian dominance over the Heptarchy, leading to l-breaking in West Saxon. The

distribution of r-breaking is explained by the uvular nature of /r/ in Old

Northumbrian, once again originally borrowed through contact with North Germanic,

whose weakened, velar variant later spread into more southerly dialects of Old

English. h-breaking, finally, is attributed to a uniformly velar nature of /x/

in Anglian dialects, introduced after first fronting under Scandinavian

influence and later extended to Saxon dialects. The

hypothesis of North Germanic > Anglian > Saxon transfer of phonetic

features, however tempting and potentially revealing, is nevertheless fraught

with danger. For it is exceedingly risky to talk in phonetic details about

phenomena as distant and incompletely attested as Old English breaking, not to

mention continental pre-invasion Germanic dialects (cf. e.g. Marchand 1991).

Evidence put forward by Smith is mainly circumstantial and rests heavily on

Modern Scandinavian pronunciation. Therefore, while undoubtedly interesting,

this part of Smith's argument cannot be viewed as anything more than an

invitation for further research[1]. On the other hand, the issue of phonetic realisations of Old English phones in itself is a very crucial one. Too often do students of Old English fall into the trap of excessive structuralism, forgetting that segments of the Old English phonological system were used in actual, oral communication. The question of phonetic detail, therefore, as well as that of Old English allomorphy, usually dismissed or ignored, have to be given the attention they deserve. Any analysis, however, should be primarily based on the internal, Old English evidence and processes, with external data playing only a secondary, supporting role. The

other theoretical implication of Smith’s

paper which raises some doubts is the shift of the emphasis for the formation of

Old English dialects to the continental period. This is one of very few attempts

at reviving Siebs’s

theory for a number of years. While in population terms the Germanic migration

can be viewed in light of the quotation from Myres (1986) provided in the paper[2],

ethnic and linguistic generalisations of the same nature cannot be substantiated

by what is known about the linguistic and social situation of fifth-century

Germania. Probably the weakest element in Smith’s

argument is the assumption of the Anglian linguistic dominance over Saxons - if

Anglian had indeed been distinct and dominant already on the continent, the

extension of Anglian features into Saxon should have taken place or at least

begun in the pre-invasion period rather than in England. Either of the two - reliance on phonetic peculiarities and the recourse to pre-invasion Old English dialect formation - would in itself require very strong evidence to support any hypothesis built around them. In tandem, the strength of evidence required increases manifold, it is the impression of this reviewer that this evidence is lacking. Therefore, Smith’s paper has to be treated as a offering a number of very interesting and promising possibilities, while not providing definitive answers. Needless

to say, the quality ofSmith’s

paper is mirrored by other contributions in the volume. Therefore, as far as festschriften

go, this one is definitely worth reading, especially as it contains something of

interest for literary and linguistic scholars alike. Marcin Krygier, School of English, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznan (Poland). (Contact the reviewer.) References: Elmer

H. Antonsen and Hans H. Hock (eds.). 1991. Stæcræft:

Studies in Germanic Linguistics, Selected Papers from the 1st and 2nd Symposium

on Germanic Linguistics, University of Chicago, 4 April 1985, and University of

Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 3-4 October 1986.

Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins. Robert

B. Howell. 1991.

Old English Breaking and its Germanic Analogues. Tübingen:

Niemeyer. James W. Marchand. 1991. ‘The sound-shift revisited: Or Jacob Grimm vindicated’ In: Elmer H. Antonsen and Hans H. Hock (eds.), 139–146.

[1] One should also not forget Howel’s work (1991), in which he presented evidence for, e.g., apical /r/ being a possible trigger for breaking-like diphthongisations. His phonetic interpretations, although in themselves open to discussion, nevertheless seemwell argued and to some extent make recourse to special phonetic developments in the cases of r- and h-breaking unnecessary. [2] Myres suggests that the Angles played a dominant role in the migrations, and that Anglian chieftains lead ‘all the northern peoples on the north German and Frisian coasts’ in their movement south.

|

|

|